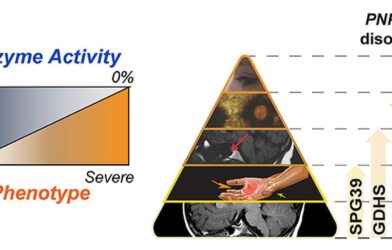

Maryland, USA: A small portion of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cases are known to be genetically determined. These include early-onset autosomal dominant AD and Down syndrome-associated AD. In these conditions, almost everyone with the associated gene variants will develop the disease. Symptoms typically begin between 40 and 60 years of age. Clinical, pathological, and biomarker changes follow a predictable sequence.

At a Glance

- People with two copies of a certain gene, APOE4, predictably developed Alzheimer’s disease from the relatively early age of 55 years.

- The findings suggest a newly defined genetic form of Alzheimer’s disease, with implications for future research, diagnosis, and treatment.

Most AD cases, however, occur later in life. Genetics alone does not determine whether someone will get late-onset AD. But genetic variations can affect the risk of developing it. One of the strongest genetic risk factors for people of European descent is a variant of the APOE gene, called APOE4. People who carry two APOE4 copies, called APOE4 homozygotes, have been estimated to have a 60% chance of developing AD dementia by age 85. While APOE4 homozygotes account for only about 2% of the overall population, they make up a larger share of AD cases—an estimated 15%.

A team of researchers led by Drs. Juan Fortea and Victor Montal at the Sant Pau Research Institute in Barcelona set out to study APOE4 homozygotes in more detail. They examined data from the NIH-funded National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center on postmortem brain pathology from more than 3,200 people with different versions of the APOE gene. The people were largely of European descent. The team complemented this with data on clinical, pathological, and AD biomarkers from five clinical studies totaling more than 10,000 people. Results of the study, which was funded in part by NIH, appeared in Nature Medicine on May 6, 2024.

Almost all of the APOE4 homozygotes in the postmortem dataset had AD brain pathology from age 55 on, compared with about half of those without APOE4. APOE4 homozygotes also consistently had high levels of AD biomarkers starting at age 55. By age 65, almost all had abnormal levels of one AD biomarker, amyloid beta, in their cerebrospinal fluid. Three quarters had detectable amyloid on brain imaging.

APOE4 homozygotes began experiencing AD symptoms around 65 years of age, on average. Mild cognitive impairment diagnosis occurred around age 72 on average, dementia diagnosis around age 74, and death around age 77. All these happened 7 to 10 years earlier than in people without APOE4.

The age of symptom onset was also less variable and more predictable in APOE4 homozygotes than in people without APOE4. The variability in age of symptom onset in homozygotes was comparable to that seen in other genetic forms of AD. Changes in biomarker levels with age followed a consistent sequence in APOE4 homozygotes as well. This, too, resembled what occurs in the known genetic forms of AD. APOE4 homozygotes did not have distinctive biomarker levels among people who had already developed dementia.

Read more

Scientists unravel genetic basis for neurodegenerative disorders that affect vision

These findings suggest that, for the population studied, AD in APOE4 homozygotes shares key characteristics with other genetically determined forms of AD. Thus, AD in these individuals could also be considered genetically determined.

“These data represent a reconceptualization of the disease or what it means to be homozygous for the APOE4 gene,” Fortea says.

The findings suggest the need for future research into diagnosis and treatment strategies specific to APOE4 homozygotes. Currently, NIH funds studies on potential treatments for people who carry two copies of the APOE4 gene. APOE4 homozygote risk also needs to be studied in populations not of European descent. NIH is actively working to increase the diversity of studies on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

-NIH news