By Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Maryland, USA: Last week brought some great news for parents of small children with type 1 diabetes (T1D). It involved what’s called an “artificial pancreas,” a new type of device to monitor continuously a person’s blood glucose levels and release the hormone insulin at the right time and at the right dosage, much like the pancreas does in kids who don’t have T1D.

Researchers published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine [1] the results of the largest clinical trial yet of an artificial pancreas technology in small children, ages 2 to 6. The data showed that their Control-IQ technology was safe and effective over several weeks at controlling blood glucose levels in these children. In fact, the new device performed better than the current standard of care.

Two previous clinical trials of the Control-IQ technology had shown the same in older kids and adults, age 6 and up [2,3], and the latest clinical trial, one of the first in young kids, should provide the needed data for the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to consider whether to extend the age range approved to use this artificial pancreas. The FDA earlier approved two other artificial pancreas devices—the MiniMed 770G and the Insulet Omnipod 5 systems—for use in children age 2 and older [4,5].

The Control-IQ clinical trial results are a culmination of more than a decade-long effort by the NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and many others to create technologies, such as an artificial pancreas, to improve blood glucose control. The reason is managing blood glucose levels remains critical for the long-term health of people with T1D.

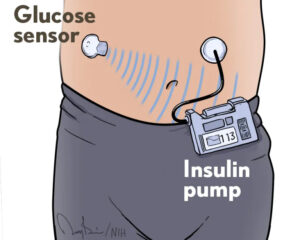

What exactly is an artificial pancreas? It consists of three fully integrated components: a glucose monitor, an insulin pump, and a computer algorithm that allows the other two components to communicate. This automation frees people with T1D from checking their blood glucose levels multiple times a day and from many insulin dosing decisions, though they still interact with the system at mealtimes.

On top of all that, these young children have a tougher time than kids a few years older when it comes to understanding their own needs and letting the adults around them know when they need help. For all these reasons, young children with T1D tend to spend a greater proportion of time than older kids or adults do with blood glucose levels that are higher, or lower, than they should be. The hope was that the artificial pancreas might help to simplify things.

To find out, the trial enrolled 102 volunteers between ages 2 and 6. Sixty-eight were randomly assigned to receive the artificial pancreas, while the other 34 continued receiving insulin via either an insulin pump or multiple daily injections. The primary focus was on how long kids in each group spent in the target blood glucose range of 70 to 180 milligrams per deciliter, as measured using a continuous glucose monitor.

During the trial’s 13 weeks, participants in the artificial pancreas group spent over 12 percent more time—approximately three more hours per day—with blood glucose in a healthy range compared to the standard care group. The greatest difference in blood glucose control was seen at night while the children should have been sleeping, from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. During this important period, children with the artificial pancreas spent 18 percent more time in normal blood glucose range than the standard care group. That’s key because nighttime control is especially challenging to maintain in children with T1D.

Overall, the findings show benefits to young children similar to those seen previously in older kids. Those benefits also were observed in kids regardless of age, racial or ethnic group, parental education, or family income.

In the artificial pancreas group, there were two cases of severe hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) compared to one case in the other group. One child in the artificial pancreas group also developed diabetic ketoacidosis, a serious complication in which the body doesn’t have enough insulin. These incidents, while unfortunate, happened infrequently and at similar rates in the two groups.

Interestingly, the trial took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, much of the training on use of the artificial pancreas system took place virtually. Breton notes that the success of the artificial pancreas under these circumstances is an important finding, especially considering that many kids with T1D live in areas that are farther from endocrinologists or other specialists.

Even with these clinical trials now completed and a few devices on the market, there’s still more work to be done. The NIDDK has plans to host a meeting in the coming months to discuss next steps, including outstanding research questions and other priorities. It’s all very good news for people with T1D, including young kids and their families.

–NIH news (NIH Director’s Blog)

Ad corner